On July 31, Governor Maura Healey signed into law legislation regarding salary range transparency (H.4890) that purports to increase equity and transparency in pay by requiring employers to disclose salary ranges and protect an employee’s right to ask for salary ranges.

The legislation is window dressing that does little to address the rampant problem of wage disparity in the Commonwealth.

The governor would have the public believe that the new law will help promote employment justice, particularly for historically marginalized employees.

“I have long supported wage equity legislation and, as Attorney General, I was proud to work together with the business community to implement the 2016 Equal Pay Act,” said Governor Maura Healey. “This new law is an important next step toward closing wage gaps, especially for People of Color and women. It will also strengthen the ability of Massachusetts employers to build diverse, talented teams. I want to thank the Legislature, advocates, labor unions, and the business community for their hard work to see this through.”

The legislation requires public and private employers with 25 or more employees to disclose pay ranges in job postings, provide the pay range of a position to an employee who is offered a promotion or transfer, and, on request, provide the pay range to employees who already hold that position or are applying for it. The Attorney General’s Office will conduct a public awareness campaign on these new rules.

This is somewhat good news if you are a white-collar employee who works for, or is applying to work for, an educational institution, a large banking chain, a tech firm, or another business staffed by the soft of hand.

Even still, the pay range is provided to employees upon request. Are these legislators completely ignorant of the imbalance of power between workers and managers that will almost guarantee repercussions against the employee who confronts their supervisor to demand this information?

Here’s the big problem, though:

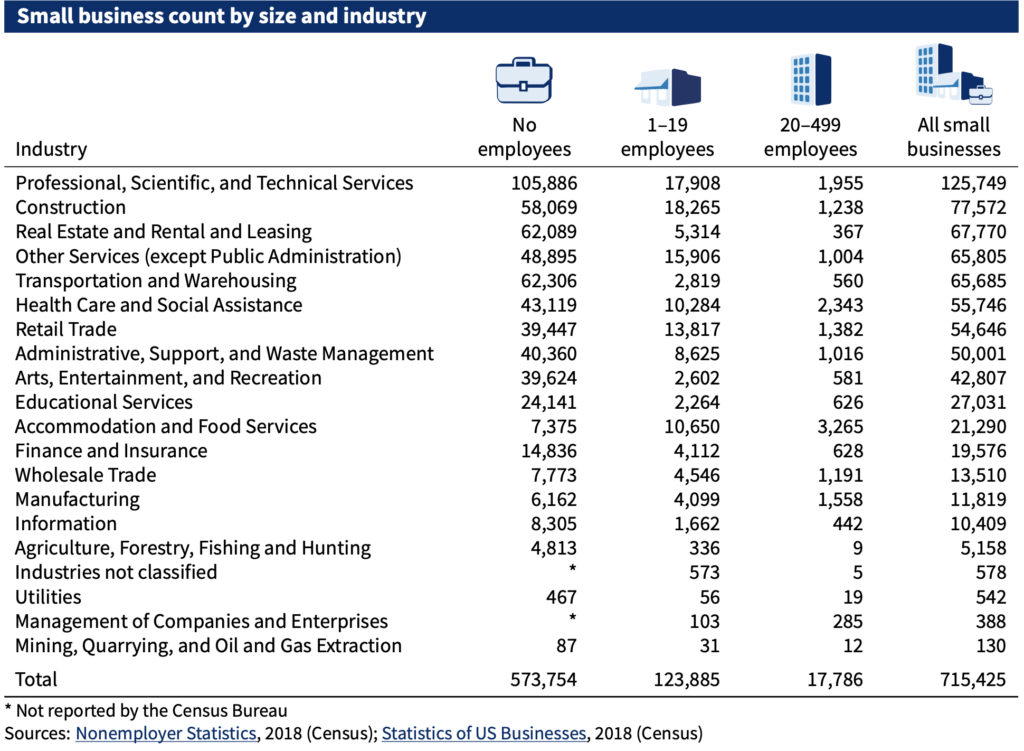

An enormous 99.5 percent of all Massachusetts employers are small businesses, according to the U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy’s “2021 Small Business Profile.”

Let that sink in—99.5 percent.

True, a small business is one with fewer than 500 employees, so one could be forgiven for thinking that, surely, this means that somewhere close to 95 percent of workers enjoy the protection this new transparency heralds. Unfortunately, you have to look at the sectors in which the workers are most vulnerable to wage secrecy and disparity.

Firstly, though, it’s important to question why the bill’s authors chose a threshold of 25 or more employees. Just about every yardstick separates small business sizes at under 10, under 20, under 100, and under 500 employees. Certainly, that’s how the U.S. Census and the Department of Labor recognize the divisions. Creating an exemption for a group of businesses with five more employees than the standard classification of “Under 20 Employees” not only pushes tens of thousands of workers out from under the umbrella of protection but also makes investigating the impact on employees by the numbers extremely difficult.

No doubt, the “hard work” for which the governor thanked the business community included lobbying hard for a measurement that would obfuscate just how meaningless the legislation would be hundreds of thousands of workers.

Healey, and all the legislators and advocates who applaud the passage of the bill, claim that women and people of color will be the recipients of all this new wage fairness. Let’s look at some of the areas where so many of the downtrodden are employed.

In 2021, in the “Accommodation and Food Services” category, 10,650 businesses employed fewer than 20 people versus the scant 3,265 that employed 20–499 workers.

“Health Care and Social Assistance” businesses with fewer than 20 people numbered 10,284 versus the 2,343 businesses with up to 499.

“Retail Trade” counted a mind-boggling ten times as many businesses with fewer than 20 staff, at 13,817, compared with 1,382 businesses with up to 499 employees.

These industries are made up disproportionately of women and people of color, often with little, or no, higher education that would lead to more lucrative careers.

Women made up 49.2 percent of workers in small business while racial minorities account for 19.6 percent, according to the “American Community Survey, 2018,” “Annual Business Survey, 2018” (Census), and “Nonemployer Statistics by Demographics, 2017” (Census).

While “Construction” is a male-dominated sector, it is also overwhelmingly powered by people of color. And yes, there are some very large companies one could name, but the fewer-than-20-workers businesses, numbering 18,265, absolutely towers over the 20–499 set of 1,238 firms—that’s a difference of more than 14.75 times as many.

When you add in those five workers to the “Under 20 Employees” category to make it “Under 25 Employees,” the volume of employees and candidates not covered by the new wage transparency law skyrockets, taking this absurd legislative deception from farce to a profane attack on women and people of color who make up Massachusetts’s struggling masses of working poor—the exact opposite of its stated goals.

Sure, employment now stands at 3,750,200 in Massachusetts, according to a report released last week by the Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development. Employees will benefit from the new law, but which employees? And in what jobs?

Except for the category “Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services” (which also employs a robust number of women and people of color), the sectors that profit from the exploitation of marginalized groups are made up of “Under-20-Employees” companies at a proportion that dwarfs those in the big business set.

Well over half a million workers, mostly blue-collar, punch the clock every day at these smallest of small businesses in Massachusetts. That the General Assembly and Governor conducted such a deception on behalf of business is a reprehensible insult to the hundreds of thousands already injured by an unjust economy.

Employers should also be required to state pay range in advertising.